Demystifying: The P2P Process

Procure-to-pay, not peer-to-peer. This is about spending money, not saving it ;)

This post is for people outside the Accounting and Procurement domains who want to have a functional conversation with P2P teams. Therefore, topics covered would be at an introductory level and there are simplifications abound. I hope to make more posts soon which deep dive into some of the concepts touched upon here, including the products and companies operating in this space. Feel free to join the discussion in the comments!

You may have heard terms like PO (not Post Office), PR (not Permanent Residency), AP (not Andhra Pradesh), MDM (that’s the full acronym) etc. thrown around by the peeps in the Accounts team or the Supply Chain team. These jargons form part of the Procure To Pay process, which is the end-to-end framework of a company’s spending. But before we go deeper into that, let’s take a quick step back to understand why this is important for business.

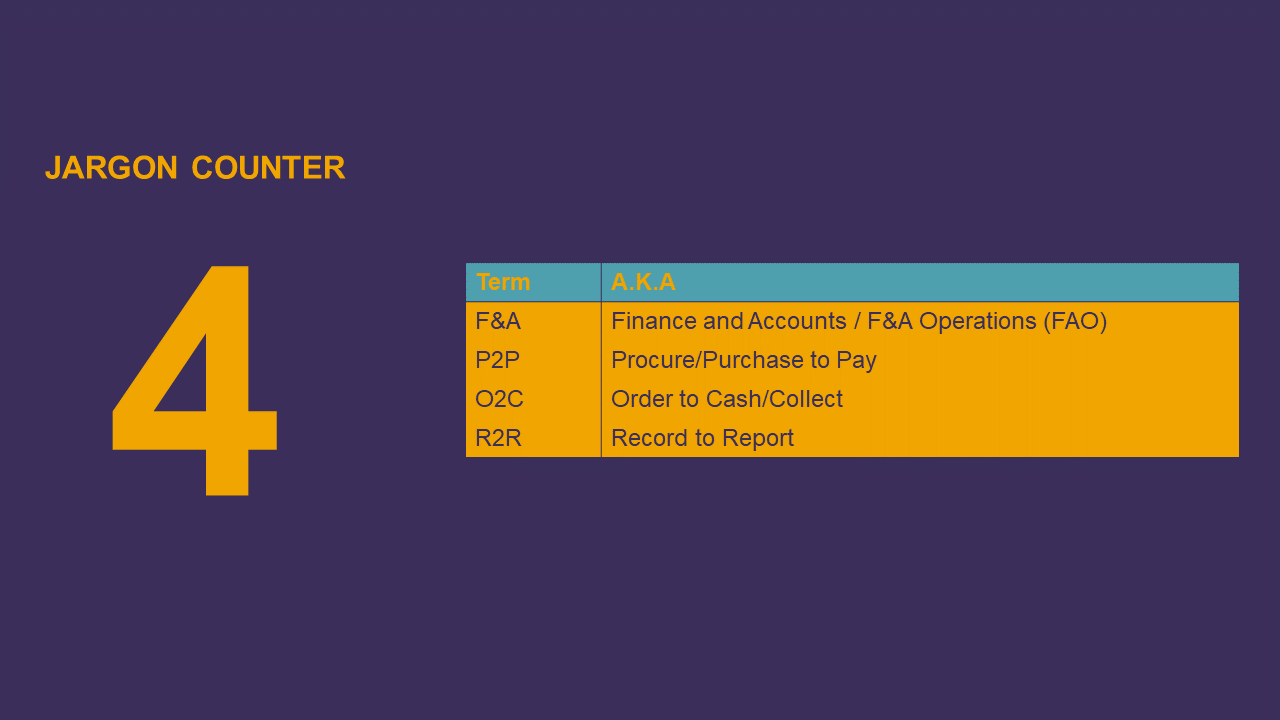

One of the best ways to understand a company is to understand how its money flows. How do they make money and what do they spend it on - i.e the bedrock of a business. How well the money is managed is often dictated by the quality of process governing it. To get a grip on the money, we can head on over to the Finance & Accounts (F&A - hey look, another acronym!) function and its three pillars:

P2P = Procure To Pay = Expense Management = What goes out

O2C = Order To Cash = Revenue Management = What comes in

R2R = Record To Report = Bookkeeping = Writing down what goes out and what comes in

Oof, these jargons are starting to add up aren’t they. Let’s setup a counter.

All three of these pillars serve an important purpose, but today we’re going to be focusing our attention on P2P. A comprehensive P2P cycle should ideally govern every single expenditure of the company. Every paisa spent needs to have a rationale behind it. This doesn’t necessarily mean every organization, large and small, needs a complicated flowchart with dozens of swimlanes, branching paths and exception handling at every step. At it’s heart, whether it’s done by several teams or just by one person, there are some key tenets of the process:

What are we paying for?

Why are we paying on this?

Who are we paying?

How will we be receiving and paying for this?

Where will we receive it?

When will we pay for it?

In an early stage startup, the process governing these is pretty much the founder’s thought process. The designer needs a new $1000 workstation with top of the line specs for just making designs on Photoshop? Sure thing man, you’re gonna get that PC (the what) because you’re my main designer and I need you happy (the why). Let me just hop on to Amazon (the who) and pay with the company card (the how we pay), enter the office address (the where) so that I get this dude his computer tomorrow (the how we receive). Easy, right?

In a larger company, it won’t be quite that simple. This is when that large flowchart looms in, with its approvals, applications, supporting documents etc. So instead of looking at that, let’s break it down with an example.

Let’s say you’re an employee of a large company. Your current chair is wretched and actively makes your life miserable. So how do you fix this? You probably ask your office admin team for a new chair. This is what we need to buy. Now let’s say the admin team doesn’t have any spare chairs laying about that they can just swiftly wheel to your desk. They have to buy a new one and that means spending money.

Just like any business decision, whether an expense is undertaken is based on whether there will be a positive Return on Investment. You’re an amazing employee (I trust you) and I need you at the top of your game. And for that, you need to sit comfortably and do your job without being bogged down by an annoying chair. This is the why of the expense. To kickstart the process formally, a Purchase Requisition (PR) is raised. It may have to be approved by your line manager so that you aren’t requesting the admin team for new chairs every month.

From here, the admin team (or in larger organizations, the baton is passed on to a dedicated Procurement team) has to decide where to get the chair from. They usually have a set of vendors for standard requirements, alternating between them to balance stability of supply and risk of over-reliance. They also have a constant stream of new vendors pitching them their products at competitive rates, so they also balance trust and price. At this point, they may issue a Request For Proposal (RFP), to which each of the vendors can respond to with the specs of the chair they’re selling and the price at which they’re selling to. The team evaluates all the responses and picks out the one that suits your need and is within budget. This is the essence of the who of the expense, the people we are buying from.

Okay great, we know the vendor, time to just pay them and get that chair to your spot, right? Maybe in a small-mid size orgs, but it’s not quite that simple in mid-large sized organizations. This is when we raise a Purchase Order (PO). A PO typically contains:

PO number and date

details of the vendor we are buying from

the quantity

the price

the delivery address

the expected delivery date

tax details etc.

It lays out the how of the expense, detailing the finer aspects of the purchase.

In some companies, this part of the P2P process starts entering the ambit of the Accounts Payable (AP) team - but more on them in a bit. To have a regular influx of chairs to keep up with the wear and tear of existing ones, they may issue something called a blanket PO. A blanket PO can be used to specify requirements round the year - say, 2 chairs to be delivered every month at the agreed price. These may be in the form of supply contracts as well. Companies procuring the same stuff for routine use rely on these to avoid the hassle of creating a new PR and PO for something they know they need regularly. It’s also entirely possible that a PO may not be required at all - low value expenses, vendors who don’t need a PO, minor one-time purchase etc. Various approval systems can be put in place to ensure that POs raised are valid and reviewed.

Most large companies use an ERP solution like SAP, Oracle, MS Dynamics etc. Why am I bringing this up? Because we’re going to take a quick detour to a process called Master Data Management (MDM). This is a core part of the process, particularly from a risk perspective in orgs that are scaling fast/already scaled large.

As the name implies, MDM pertains to managing data, but specifically, metadata. This encompasses all the base data of vendors, customers, employees and materials. The stuff that wouldn’t change transaction to transaction. Having a vendor master will enable teams to make POs and payments to the same vendor much quicker, without having to enter all of the above data every time we purchase something from them. If we are buying a chair from a vendor, data about the vendor needs to be in the system such as the name of the vendor, contact details, their bank account, their preferred mode of payment and something called a credit period. Credit period refers to the number of days that the invoice can be unpaid. In the chair example, a 30 day credit period implies that you have to pay for the chair within 30 days of the invoice date. The importance of the credit period will be highlighted later on.

The when of the expense is rather tricky as the next steps vary wildly based on the type of product, type of customer (B2B vs B2C), recurrence, existing contracts etc. Let’s go with invoicing as the next step. The vendor will then send your AP team an invoice, which the team accesses via mail or a workflow tool. From there, it’s entered into the ERP/accounting software as a purchase made. With automation and Optical Character Recognition (OCR) tools available aplenty, documenting the invoice is now easier than ever. The invoice usually has the:

invoice number, date and amount

the products ordered and the quantity

their bank account number

tax details (GST, VAT, TDS etc.)

PO number

payment due date etc.

As part of the invoice processing, AP teams often tag each invoice to a Cost Center (CC). This is to get a CC-wise Profit & Loss statement. In this example, we would be tagging the chair invoice to the Development team’s CC and at the end of each month, we can see how much we spent on just the development team by extracting a report of the development team’s CC.

Oh hey modern day Santa Claus is here - the delivery guy has arrived! The admin team goes to the gate, has a look at the chair and takes delivery of it. They do the last part by taking a receipt of something called a Goods Receipt Note (GRN). If you’ve ever received a courier delivery or ordered something online, you might’ve signed a slip - that’s the GRN. The GRN lays out the item being delivered, the quantity that is being delivered, who it is being delivered to and when it was delivered. We now have the where of the expense as well. This is important because in larger manufacturing setups, goods will be received at various godowns, factories and warehouses.

You got your chair now, but there’s just one tiny thing left - the payment. If this order was prepaid, then we would’ve received the chair after payment. In some cases, like with regular suppliers to a factory, invoice may come after delivery of the goods and lumpsum payments would be made at the end. So the progression between invoice, GRN and payment is never straightforward and looks something like this:

The above picture also captures an important check that companies perform prior to paying: Three-way matching. In short, this refers to making sure the details in the Invoice, GRN and PO all match with each other. That what we ordered = what we got = what we are billed for. Most ERPs have this match automated or at the very least, available as an option.

Let’s assume we haven’t paid yet for our chair. In most situations, payments are sent out when it “becomes due” i.e when the credit period ends. While smaller companies disburse payments as and when they see fit, larger companies usually have scheduled payment days for each week and month. So they compile all the dues that are to be disbursed and send it out on these specified days. This is what is referred to as a payment run. But why wait till the end of the credit period? Why not disburse the money as soon we receive the product or the invoice? Can we not pay something even after its credit period is over?

This is where the payments process ties into a concept called Working Capital (WC) management, which broadly means balancing its what can we spend now vs what we owe now. Essentially, the company has to play a game of how long they can hold on to payments before they haaaave to be made. Because they can better utilize the cash in hand now for other purposes than just paying it to the vendor. To incentivize early payments, vendors often provide discounts to customers who pay before the due date.

Once all the payments are ready to go, all the invoices are marked as paid in the ERP and the company disburses the money (via a bank portal, cash or cheques). From here on, the P2P process streams further into finer concepts of quality audits, analysis, accounting etc. but those are topics for another time.

If you’ve made it through the journey, nice! Here’s a snapshot of the journey we just went on:

Services also adhere to this funda, just in different ways. Case in point: You can’t really have a GRN for a service, because well, it isn’t “goods”. Instead services usually have milestones, upon reaching which payments become due. If you hire someone to paint your house, you would say you’d pay him 50% when he finishes the bedrooms and the rest when he finishes the living room and kitchen. The completion of painting of the bedrooms is the milestone and you have effectively “received” the service to that extent. Meaning it’s time to pay up half.

P2P systems are now automated at various levels and vary based on industry, size, complexity and many other factors. So things like PRs might have multiple levels of approvals in some companies, while they may be a foreign concept in others. But a good P2P system always addresses the key questions which we’ve gone through in the post, regardless of how sophisticated the system is.

Finally, here are all the terms we went over:

All that for a chair. Phew!